Chapter 1 : Icons 1950-1959

Time

The passage of time always changes things. It creates layers to memory that alter events in one way or another, memories that were clear become less so and become byproducts of our emotions. things we like become better, feel better and our memories of them are altered forever. The same things happen with the things we don’t like, our memories amplify our negative feelings and create distance and discomfort.

This project is an effort to learn things I didn’t know and share them. To take fond memories of a sport I love and turn them into information in order to transport people young and old back to a time in the world were sports were important not just because of how much money you could be made playing them. Back to a time were the playing of a sport could change society in ways that religion & politics always seemed unable to.

But most of all this is just a way for me to share shit I like with anyone who chooses to read it. This first chapter is about events that happened before I was born, it’s not heavily researched and most of the historical text and photos can be found by simply googling the subject. But I will do my best to add some of myself to it and entertain so reading it will be worthwhile.

Enjoy

Basketball is a mirror

If you really pay attention to basketball’s history you will discover a few interesting patterns. The most obvious one is that in the sport of basketball the stars were always stars, the truly dominant players are dominant on every level for the same reasons. Basically they are what they are and there is no in between. The other obvious pattern is Basketball more than any other major sport mirrors society, all of humanity’s strength, ignorance, perseverance love, hate greed, loyalty, determination, tolerance or lack thereof is readily on display for all to see. Other sports are capable of hiding themselves whether it be behind tradition, nationalism or spectacle, so their true faces can’t always be seen but Basketball is a mirror and no matter how much we try to ignore the truth about ourselves, looking directly into a mirror always shows you exactly what you look like. Leaving the important question for each of us to answer…

will we be honest about what we see?

1950 -CCNY The First and Last

The City’s Game

In the early years of college Basketball recruiting was not the national enterprise it is now, in the 1950’s recruiting was more of a regional endeavor and schools did most of their recruiting locally. Because of this fact the 1950 City College of New York Beavers roster reflected the population from the sidewalks of New York city. Their starting 5 consisted of 2 black & 3 jewish players from the city’s public high schools making them the first college team to have Black players in their starting lineup. CCNY was called the poor man’s Harvard because of the schools high academic standards, but unlike Harvard their students were from regular working class New York families. Coming from schools in the 5 Boroughs like Dewitt Clinton in the Bronx and Erasmus High School in Brooklyn (ADD MORE) that juxtaposed with the fact that the Beavers played their home games in Madison Square Garden, a professional arena and not an on campus gymnasium at a time when college basketball was more popular than the NBA is an interesting factor and has bearing on the ultimate outcome of the CCNY story. Attendance for CCNY games often reached 18,000 fans which more than doubled that of the New York Knickerbockers, New York’s professional team so when there were scheduling conflicts the Knicks games were moved to the dilapidated 69th Regiment Armory on 23rd street and the CCNY team got to play in a fancy professional arena filled to capacity.

The ethnic composition of the team, the famous place they played their games, and the other unique factors that playing in New york City at this distinct time in history provided created a volatile mix of excitement and interest which has never really been duplicated.

Coach Nate Holman and the 1950 CCNY team

Beating the Baron

The 1950 National Invitational Tournament, more commonly known as the NIT was the more popular and prestigious national tournament at this time in college basketball and the fact that the tournament was held in Madison Square Garden was an advantage for the Beavers. In Round one CCNY defeated the University of San Francisco who had won the NIT in 1949 65-46. in the second round CCNY faced the mighty Kentucky Wildcats. Kentucky had just won back to Back National Championships in 1948 & 1949 under legendary Coach Adolph “the Baron” Rupp.

At the time schools in the south like Kentucky were racially segregated. The college teams in theSEC (Southeastern Conference) which Kentucky belonged to was like most southern conferences at that time, segregated. So most southern teams weren’t used to facing teams that fielded black players. Some teams even refused to take the floor against teams with black players so facing a team with multiple black and Jewish starters was not a common occurrence.

Prior to the game some of Kentucky’s players refused to shake hands with CCNY’s black and Jewish players needless to say this enraged the Beavers, and fueled by that anger the CCNY squad defeated Kentucky 89-50 Which ended up being the worst defeat of Adolph Rupp’s career. The blowout win over Kentucky was made to seem even more impressive due to the fact that CCNY had interrupted what would end up being a 4 year run of dominance from Rupp’s Kentucky program. Kentucky had won the NCAA tournament in 1948, 1949, and would win the tournament again the following year in 1951 but CCNY handled them easily. The Beavers then followed their impressive win by defeating the highly ranked Bradley Braves in the final to win NIT championship.

NCAA Title Run

After CCNY's run to the NIT title, the Beavers were immediately selected to participate in the NCAA Tournament. In the first round, City College nipped second ranked Ohio State, 56–55. The Beavers then defeated fifth ranked North Carolina State 78–73 to reach the title game where CCNY again faced top-ranked Bradley and won the tournament, 71–68, CCNY's victory was voted the most exciting event in the history of college basketball at wait for it …Madison Square Garden.

The 1950 CCNY Beavers remain the only team in college basketball history to win both the NIT and NCAA tournament in the same year and they won both finals on their home court.

Madison Square Garden!

1951 Fall From Grace

In early 1951, with CCNY's grand season still fresh in the city's memory, CCNY was implicated in a point-shaving scandal. Seven Beaver players, Herb Cohen, Irwin Dambrot, Floyd Layne, Norman Mager, Ed Roman, Al Roth and (NEED 1St NAME)Warner--were arrested and charged with conspiring to fix games. The CCNY players were hardly alone. Some 30 players from six schools around the country, including powerhouses Kentucky and Bradley, would also be snared in the web. it was found that the players had taken money from gamblers in the point-shaving scandals during the 1948–1949 season and also during some regular-season games in the 1949–1950 season. However there was no evidence games were fixed during the postseason tournaments but the damage was already done because the guys from CCNY were hit the hardest since the scandal ended their NBA hopes and forever tarnished the 1949-50 team's legacy.

A heavy price to pay

The scandal sent shock waves throughout college basketball and prompted the suspension of the CCNY basketball program. The Beavers program was demoted from Division I to Division III and was banned from ever playing at Madison Square Garden again. As a result of these sanctions, the CCNY basketball program was de–emphasized, and the school has never again appeared in either the NCAA or NIT tournaments.

To this day CCNY is also the only NCAA Basketball Championship winning team that is no longer a member of Division I.

This might be related to the point-shaving scandal of 1951 and the existence of gamblers in New York City but the NCAA tournament did not have another game at any Madison Square Garden facility from the 1961 tournament until 2014, when its successor, Madison square Garden IV, hosted the East Regional Finals.

the scandal of 1951 was a sad end to the most exciting year of College Basketball in the History of New York City

2 Blacks Max

Bill Russell and the 1955 & 1956 University of San Francisco Dons

Looking back one of the major negative aspects of early years of sports in this country was racism and college basketball was no different. Since around the 1930s there was a practice ironically called a Gentleman’s Agreement” were professional leagues and universities that played college sports agreed not to play black players especially when games were being played in the South. During the1950’s a lot of schools “agreed” not to play more than two black players at a time. But fortunately for the world and for everyone else the University of San francisco chose not to honor that agreement. so in the 1955 in 1956 seasons University of San Francisco Dons (one of the coolest team nicknames ever by the way ) chose to start three black players Bill Russell, K.C. Jones and Hal Perry. which marked the 1st time in NCAA history 3 black players started a game together. The Dons, like most teams of that era recruited their players locally from the San Francisco / Oakland area and promptly won back to back championships.

1956 San Francisco Dons Left to right K.C. Jones Mike Farmer ,Bill Russell Carl Boldt and Harold Perry

Dominance of the Dons

The 1955 & 1956 University of San Francisco teams led by Coach Phil Woolpert and Bill Russell were dominant going 28-1 in 1955 and 29-0 in 1956. The Dons won 55 consecutive games over those 2 seasons but unfortunately the Dons success on the court did not change the way society treated their black players off the court. During one season the Dons were playing in a tournament in Oklahoma City and the hotel the team booked refused rooms to the black players. In a show of unity that serves to prove that sports, respect and love have the power to change hearts and minds all the San Francisco players both black and white, along with their coaches camped out at a nearby dorm rather than stay at the hotel that would not accept their teammates. This became something common in both collegiate and professional sports during the 1950’s and 60s.

Soon after USF won their Back to Back National titles other schools around the nation washed their hands of the “Gentleman’s agreement” and started recruiting and fielding teams that featured African American Players.

Bill Russell

The most accomplished basketball Player ever .

During his college career Bill Russell’s ability to grab offensive rebounds led to what was called “The Russell rule” which included the expansion of the lane to 12 feet in an attempt to keep Russell further away from the basket. Offensive goaltending, also called basket interference, was also introduced as a rule in 1956 because Russell was athletic enough to consistently play above the rim. Russell who was 6’9” and agile was still able to dominate the boards on both sides of the ball despite the NCAA literally altering the actual court configurations just to limit his success.

Bill Russell was voted MVP of the Final Four in both 1955 and 1956. in 1955 Russell averaged 21.4 points and 20.5 rebounds and during his senior year he averaged 21 points and 21 rebounds per game. he went on to win an Olympic Gold Medal in 1956 and 11 championships in 13 years as a Pro, thats 14 championships in 16 years a record that is unmatched.

He also became a Player Coach later in his pro career and was a prominent figure in the civil rights movement and will always be a Sports icon

1956-1958 Elgin Baylor, Coast to Coast.

The Road less traveled

Despite his success as a high school basketball player at several segregated black schools in Washington DC, no major colleges recruited Elgin Baylor because at the time, major college scouts did not recruit players from all black high schools.

While some colleges were willing to accept Baylor, he did not qualify academically. A friend of Baylor's who attended the College of Idaho helped arrange a football scholarship for Baylor for the 1954–55 academic year so Baylor enrolled at the College of Idaho but Baylor never played football for the school, instead, he was accepted to the college's basketball team without having to try out. After the 1955-56 season, the College of Idaho dismissed its head basketball coach and rescinded Baylor’s football scholarship. in 1956 A Seattle car dealer interested Baylor in Seattle University, and Baylor sat out a year to play for Westside Ford, an AAU team in Seattle, while he established academic eligibility at Seattle.

On The Court… Finally

During the 1956-57 season, Baylor averaged 29.7 points per game and 20.3 rebounds per game for Seattle University. The next season 1957-58, Baylor averaged 32.5 points per game and led the Chieftains (another cool team name even if it’s politically incorrect the team is now known as the Redhawks by the way) to the NCAA Championship game, Seattle's only trip to the Final Four, falling to the Kentucky Wildcats and Adolph Rupp. Following his junior season, Baylor was drafted again by the Minneapolis Lakers, with the No. 1 pick in the 1958 NBA Draft and this time he opted to leave school to join the Lakers for the 1958-59 season .

College Career

Over three collegiate seasons, one at College of Idaho and two at Seattle University, Baylor averaged 31.3 points per game and 19.5 rebounds per game. He led the NCAA in rebounds during the 1956–57 season and led Seattle University to their only final four appearance (1957-58)in the schools history.

Replica of Elgin Baylor’s

University of Seattle Home Jersey

The Big Dipper changes the game 1956-1958

National Recruit

I’ve made mention of the mostly regional recruiting that was prevalent during this 1950’s & 60’s but After his last High School Season at Overbrook High in Philadelphia, more than 200 universities tried to recruit Wilt Chamberlain. UCLA offered Chamberlain the opportunity to become a movie star in Hollywood , the University of Pennsylvania allegedly wanted to buy him diamonds, and Cecil Mosenson, Chamberlain's coach at Overbrook, was offered a coaching position if he could persuade Chamberlain to accept an offer to the scholl. But Chamberlain wished to experience life away from home, so he eliminated colleges from the East Coast; he also ruled out the South because of racial segregation; and Chamberlain felt West Coast basketball was of a lower quality than in other regions which ruled out the california schools so after visiting KU and talking with the school's legendary coach Phog Allen, Chamberlain announced he was going to play college basketball in the Midwest at the University of Kansas.

Supreme Athlete

After enrolling at Kansas, Chamberlain displayed his diverse athletic talent. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10.9 seconds, shot-putted fifty-six feet, tripled jumped more than fifty feet , and won the high jump in the Big Eight Conference track-and-field championships in three consecutive years.

Chamberlain performing the High jump for Kansas track and Field

Hardwood Debut

On December 3, 1956 Chamberlain made his varsity basketball debut as a center for the Kansas Jayhawks. (in my opinion another cool assed team nickname) In his first game, he scored 52 points and grabbed 31 rebounds, breaking both all-time Kansas records in an 87–69 win against the Northwestern Wildcats

More rule changes

As it had with Bill Russell the introduction of another highly athletic African American Player prompted The NCAA to implement immediate rule changes and Chamberlain ended up being the catalyst for several 1956 NCAA basketball rule changes, including an almost unbelievable one that we take for granted today, the requirement for a shooter to keep both feet behind the line during a free-throw attempt. Chamberlain was a poor free throw shooter, and like a lot of stories concerning Chamberlain’s athletic prowess this may be apocryphal but Chamberlain was reported to have had a 48-inch vertical leap, so by beginning his movement just steps behind the top of the key Chamberlain was capable of converting foul shots by dunking the ball without a running start, hence the free throw line rule. In addition, an inbounds pass over the backboard was also banned because of Chamberlain.

Disappointment

In 1957 The Kansas Jayhawks were one of twenty-three teams selected to play in the NCAA Tournament. The Midwest Regional was held in Dallas, Texas which at the time was segregated. In their first round game, the Jayhawks played the Dallas based, all-white Southern Methodist University Mustangs and The crowd was brutal. The Jayhawks players were spat on, pelted with debris, and subjected to the vilest racial epithets possible. KU won the 73–65 in overtime, and the Jayhawks had to be escorted out of the arena by police. The same thing happened again in the next round in Oklahoma city but Kansas won 81-61 despite the poor treatment. Chamberlain led the Jayhawks to the national championship game and lost the game to North Carolina in Triple overtime. Despite the loss, Chamberlain, who scored 23 points and 14 rebounds in the game, was elected the Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four which was no consolation because Chamberlain considered it the most painful loss of his life.

Frustration

During Chamberlain's junior season of 1957–58, the Jayhawks' matches were increasingly frustrating for him. Knowing how good he was, opponents resorted to freeze-ball tactics and routinely used three or more players to guard him. Teammate Bob Billings commented, "It was not fun basketball ... we were just out there chasing people as they were throwing the basketball back and forth"

Chamberlain averaged 30.1 points for the season and led the Jayhawks to an 18–5 record and three of the team’s losses came while he was out with a urinary infection. The Jayhawks' season ended because KU finished second in the league and only conference winners were invited to the NCAA tournament.

Jayhawk Career

In two seasons at KU, Chamberlain averaged 29.9 points and 18.3 rebounds per game while totaling 1,433 points and 877 rebounds, Despite only playing in 48 games and last playing in 1958, Chamberlain's 877 rebounds is still 8th all-time in Kansas Basketball history

Chamberlain as a Harlem Globetrotter

Globetrotter

After his frustrating junior year, Chamberlain wanted to become a professional player. At that time, the NBA did not accept players until after their college graduating class had been completed, so Chamberlain decided to play for the Harlem Globetrotters in 1958 for $50,000 ending his career as a Jayhawk.

(CHAMBERLAINS PRO ACCOMPLISHMENTS GO HERE)

Zeke from Cabin Creek

One of Jerry West’s many nicknames Zeke from Cabin Creek was derived from the Creek in West Virginia where West grew up.

Jerry West, West Virginia 1957-1960

1959

During his junior year (1958–59), West scored 26.6 points per game and grabbed 12.3 rebounds per gamea s a guard. He tied the five-game NCAA tournament record of 160 points (32 points per game) and led all scorers and rebounders in EVERY West Virginia game, including getting 28 points and 11 rebounds in a 71–70 loss to California in the tournament final. West was named Most Outstanding Player of that year's Final Four (ADD MORE)

The Big “O”

Record Setter

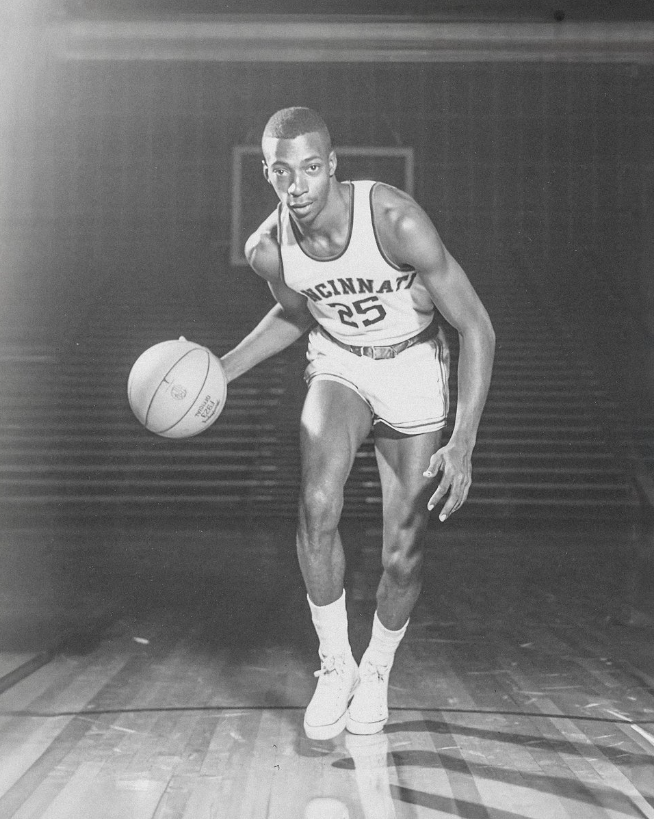

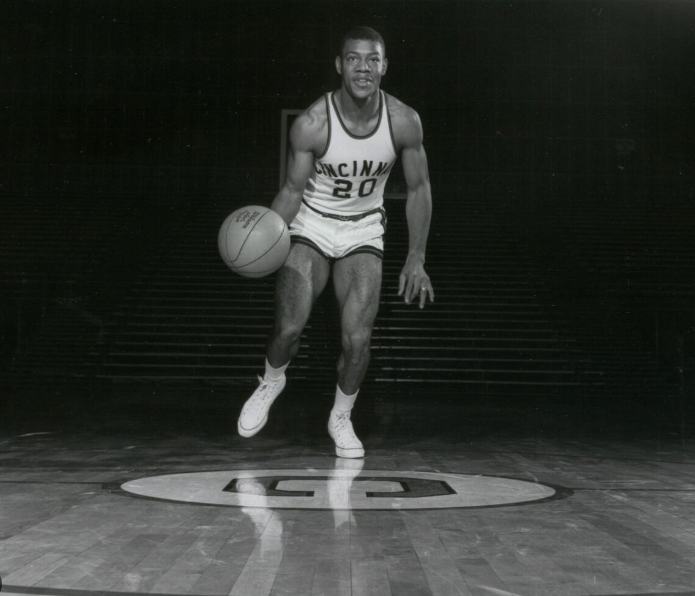

While Playing for the Cincinnati Bearcats, Oscar Roberston recorded a scoring average of 33.8 points per game, the third-highest in college basketball history. In each of his three years, he won the National Scoring Title, was named an All-American, and was chosen College Player of the Year, while setting 14 NCAA and 19 school records.

The Best of the Best

Oscar Robertson soars for a rebound against Kansas state

Robertson had many outstanding individual game performances, including 10 triple-doubles. His personal best may have been his line of 45 points, 23 rebounds, and 10 assists against Indiana State in 1959. Despite his success on the court, Robertson's college career was soured by racism In those days, Southern university programs such as Kentucky, Duke, and North Carolina did not recruit black athletes, and road trips to segregated cities were especially difficult, with Robertson often sleeping in college dorms instead of hotels. Years later, he told The indianapolis Star "I'll never forgive them." Decades after his college days, Robertson's stellar NCAA career was rewarded by the United States Basketball Writers Association when they renamed the trophy awarded to the NCAA Division I Player of the Year the Oscar Robertson trophy in 1998. This honor brought the award full circle for Robertson, as he had won the first two awards ever presented.

Oscar Robertson’s

1959 Home Jersey

Bearcat Career 1957-1960

Robertson's stellar play led the Bearcats to a 79–9 overall record during his three varsity seasons, including two Final Four appearances; however, a championship eluded Robertson, When Robertson left college, he was the all-time leading NCAA scorer. Robertson took Cincinnati to national prominence during his time there, but the university's greatest success in basketball took place immediately after his departure, when the team won national titles in 1961 and 1962, missing a third consecutive title in 1963 by just two points. He continues to stand atop the Bearcats' record book and the many records he still holds include points in one game at 62 (one of his six games of 50 points or more), career triple-doubles at 10, career rebounds per game at 15.2, and career points at 2,973.

CONCLUSION TO CHAPTER ABOUT ICONS

Chapter 2: The Battle of Buckeyes and Bearcats - 1960-1962

1960 - Big Time Buckeyes

Shown below 1960’s Ohio state shooting shirt

Forgotten Greatness

For some reason the 1959- 1960 Ohio State Buckeye team is not a celebrated group and on the surface it doesn’t seem quite fair. in the 1950’s 60’s and 70s freshman weren’t allowed to play varsity so the 1960 ohio state team should be more well known because The recruiting class of Jerry Lucas, Mel Nowell, John Havlicek, Bobby Knight, and Gary Gearhart were not eligible to lead the Buckeyes until 1959–60. This was their first college season of play and along with Junior guard Larry Siegfried this core group lead the team to the championship in 1960 and finals appearances in the1961 & 1962 seasons. They should also be more well known because 3 of their players are Basketball Hall of Famers, Lucas & Havlicek as College & NBA Players and Bobby Knight as a Coach at the University of Indiana.

Bobby Knight was a reserve guard at Ohio state from 1960 - 1962

Jerry Lucas

A Different Style

The 1959–60 team posted the best shooting, highest-scoring team in college basketball that season at over 90 points per game. The key to the attack was the rebounding and outlet passing of Lucas. The other four athletes routinely overwhelmed opponents with fast break baskets. In 1960, this kind of offensive play was considered on the cutting edge of the game, and a big reason why all five starters were later drafted into the NBA. There were only eight NBA teams at this time, so this was not an easy feat.

The Buckeyes steamrolled through the NCAA tournament by an average of 19.5 points a game, dusting off defending national champion California 75–55 in the final behind their two future NBA stars, Jerry Lucas and John Havlicek, two excellent guards in Larry Siegfried and Mel Nowell and a defensive work ethic that limited opponents to .388 shooting over the course of the season.

Jerry Lucas

1959-60 Home jersey

John Havlicek grabs a rebound against Northwestern University

1961 & 1962 Bearcats Back to Back

1960-61 Cincinnati bearcats

In the 1961 NCAA Tournament the Cinncinati Bearcats led by first year coach Ed Jucker reached their first ever tournament final after having lost in the Final Four in back-to-back years despite being led by their transcendent star Oscar Robertson.

In the Final they faced rival Ohio State, who with their roster of Jerry Lucas, John Havlicek and Larry Siegfried along with Coach of the year award winner Fred Taylor returned to the final as the defending champions. The Bearcats trailed Ohio State 39–38 at halftime and their defense rattled Ohio State stars Lucas and Havlicek to tie the game 61–61 at the end of regulation. Cincinnati played slow control in overtime to win 70–65 for the program's first national championship.

In the 1962 NCAA Tournament they met Ohio State again in the National Championship, after rolling through the tournament with only UCLA playing them close (a 72–70 win). They blew out Ohio State (hindered by injury to Lucas) 71–59 to clinch back-to-back NCAA Tournament championships.

Bearcats from left to right Bob Wiesenhahn, Tom Thacker, George Wilson, Tony Yates

Cincinnati Basketball & Coach Jucker Overlooked by History

Most people know that Oscar Robertson starred for the Bearcats from 1957-1960 but it may surprise some that the University of Cincinnati Men’s Basketball Team is one of the winningest programs in NCAA history. During their glory years (1958 -1963) they compiled an insane record of 161-16 with 5 consecutive Final Four appearances and 2 National championships.

Under Coach Ed Jucker Cincinnati lost just six times in his first three seasons. His 1963 team lost only one regular season game before losing the 1963 NCAA tournament final in overtime against Loyola of Chicago ending the Bearcat Dynasty. Coach Jucker holds the record for the highest winning percentage (.917) in NCAA tournament play. In his five seasons coaching the Bearcats, Jucker's teams posted a record of 113–28, a .801 winning percentage that’s pretty damn good!

Chapter 3: The Winds of change

America 1962

In 1962 the Country, and the South in particular, was torn by civil rights protests with education at the center of the turmoil. By the fall of 1962, racial tension had exploded in the American South. Groups such as the Little Rock Nine and the Freedom Riders had exposed the violence . Spurred by the deep-seeded biases of many Americans and the need for change, James Meredith a black man who was born in Kosciusko, Mississippi, had intently followed the escalated resistance and believed that it was the right time to move aggressively in what he considered a war against white supremacy. The day after President John F. Kennedy took office in the White House Meredith began the struggle to attend the all-white University of Mississippi with his mailed request for a brochure and application. The ensuing events instigated a political battle that would lead to the direct involvement of Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and the president of the United States. Two times Meredith attempted to register and two times the university rejected his application. Both times Governor Barnett presented official proclamations denying his entry to the university. Barnett even tried to prevent Meredith’s enrollment by assuming the position of registrar and personally blocking his admission to the school. Meredith eventually filed suit with the assistance of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund. After a protracted court battle, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Sept. 10, 1962, that Meredith was to be admitted to the university.

On Sept. 30, 1962, when a deal was reached between Barnett and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to allow Meredith to enroll, a riot broke out on campus. A mob of angry whites confronted U.S. marshals stationed on campus to protect Meredith. The crowd assaulted the marshals with bricks and bullets outside the Lyceum, the university’s administration building, until the arrival of federal troops quelled the violence in the early morning hours. Two bystanders died in the confrontation, 206 marshals and soldiers were wounded, and 200 individuals were arrested. Meredith was finally allowed to register for courses on Oct. 1, 1962

James Meredith

Mission Accomplished : On August 18, 1963, Meredith fulfilled his childhood dream and graduated from the University of Mississippi with a degree in political science.

1963

By 1963, other colleges across the South like Clemson, Tulane and Southwest Texas State were beginning to admit their first black students, those transitions to desegregation were more peaceful. but Southern basketball teams remained strictly segregated. And unfortunately many coaches at schools that had integrated teams all across the country were involved in (yes I’ve mentioned this before) a gentleman’s agreement not to play more than two black players at a time. and in some road games, black players would have to rotate so that only one of them was playing at any given moment.

Loyola University Chicago and their coach was one of a few that ignored this practice, During the 1962-63 season, Loyola Coach George Ireland defied the unspoken rule and started not 1, not 2, not 3 black players. Of Loyola University Chicago’s five starters Ron Miller, Jerry Harkness, Vic Rouse, Les Hunter, and John Egan, 4 were black only Egan was white. And when he was subbed out, Loyola would have five black players on the court.

The Loyola Ramblers (another great team name!) started the season ranked #4 in the country and won 21 straight games before suffering their 1st loss and Loyola finished the regular season 24-2 and entered the NCAA Tournament ranked #5 in the country.

In the Tournaments 1st round the Ramblers destroyed Tennessee Tech 111-42 to set up a meeting with 7th ranked Mississippi State in the round of 16, the only problem was no one could be sure that the game would be played. The biggest thing at the time," said Harkness, a two-time All-American, "is we didn't know if they were coming." coincidentally neither did Mississippi State.

Governor Barnett…Again,

Playing, at least in big games, had been a big problem for the MSU for years. On the court Mississippi State had won the SEC championship in 1959, 1961 and 1962, but each year, the Maroons (now known as the Bulldogs) watched Kentucky represent the league in the postseason, because of an unwritten but strictly enforced Mississippi rule that prohibited state schools from playing against integrated teams. Governor Ross Barnett, an avowed segregationist, made no secret of his stance concerning the game. and declared that The Maroons were not to leave Mississippi. But buoyed by an angry fan base that was tired of seeing its team stay home while Kentucky competed, and an equally fed-up coach in James "Babe" McCarthy, Mississippi State president Dean Colvard vowed to let his team play."It had begun to look as if our first major racial issue might pertain to basketball rather than to admissions," Colvard later said. "Although I knew opinion would be divided and feelings would be intense because of the unwritten law, I thought I had gained sufficient following that, win or lose, I should take decisive action." when told of the unwritten rule Loyola Coach George Ireland said “I feel Mississippi State has a right to be here, no matter what the segregationists say. They may be the best basketball team in the nation and if they are, they have a right to prove it."

The state was not convinced and backed by the university board, wouldn't give in so easily. so when Senator Billy Mitts, a former Mississippi State student body president and cheerleader, convinced a judge to issue a temporary injunction to prevent the team from leaving an unwritten rule became a written one.

The Great Escape

After all this in perhaps the best end-around in sports history, Colvard directed McCarthy to head for the Tennessee state line and stay in Memphis while he traveled to Alabama to try and prevent the injunction from being served. The next day, an assistant coach took the freshmen and some of the reserve players to a private plane as decoys and, when they saw that the coast was clear, called for the rest of the team to join them. That was the nerve-racking part," the assistant coach said "We didn't have our coach. We didn't have half our team. We didn't know if we were going to be able to play the game. It was Dr. Colvard and Coach McCarthy. Those two men had the backbone."

The private plane carrying the players arrived in Nashville, where McCarthy and athletic director Wade Walker had flown to from Memphis. Reunited now, the MSU traveling party flew a commercial flight to East Lansing, Michigan to play the game.

No Strangers to Racism

Meanwhile in Chicago, the Rambler players were quickly getting an idea of what they were up against. Hate mail arrived in the dorms some directly from Ku Klux Klan members. Loyola had been through its own racial strife before. Coach Ireland loved showing up southern teams and had already taken his squad to New Orleans and Houston, where they were met with less than warm receptions. In New Orleans, the black players had to stay with other black families, sequestered from their teammates, and in Houston, fans spewed racial slurs and hate from the stands. But printed letters arriving directly in the dorms was worse."That was personal," Harkness said. "They know where you are, where you live. It was frightening." Eventually Coach Ireland had the mail forwarded directly to him so the effect on the players would fade the closer they got to the game.

"The Game of Change

So in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, the Loyola Ramblers men’s basketball team and the Mississippi State Maroons became part of history

Loyola’s Jerry Harkness and MSU’s Joe Dan Gold shake hands prior to the game.

When Jerry Harkness extended his hand to Joe Dan Gold before the ball was tipped, the glare of the popping flashbulbs nearly blinded both men and they knew this was more than just another game. Everyone understood then what was happening, what it meant that Gold, a white basketball player from Mississippi State, was shaking hands with Harkness, an African-American player from Loyola Chicago on a March day in 1963 in East Lansing, Michigan the handshakes between Mississippi State and Loyola players proved to be a powerful moment in college basketball history

So what really happened in the game? Nothing and everything. Both teams played a very hard, very aggressive, very clean game, there were no fights during the game no riots after the game there was no drama.

God bless those kids," MSU assistant coach Shows said. "We had no fans there, but someone played our fight song. I'll never forget that.""We did it together," Harkness said. "To me, that's why it's so important. We showed you could do it together, without a fight."

Loyola won the game 61-51 and Mississippi State returned home to a surprisingly warm reception from fans. Shows remembers the plane flying over the highway and seeing bumper-to-bumper traffic below, with throngs of people driving to the airport to greet the Maroons. A postgame newspaper survey found that Mississippians were overwhelmingly in favor of letting the team play the game. Colvard kept his job, as did McCarthy. The game didn't usher in dramatic change immediately. The SEC wouldn't welcome its first black basketball player until 1967, when Perry Wallace played for Vanderbilt, but progress was made.

Just five months earlier, with U.S. marshals and federal troops on hand to quell the rioting, James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi, integrating the school only 90 miles from MSU's campus

Less than a month after the game, Martin Luther King Jr. would write his famous "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," an influential essay that spread across the nation.

In between these two seminal moments in civil rights history, a team from Starkville, Mississippi snuck out of town, defying a state injunction to play a basketball game against a team from Chicago, Illinois with a largely African-American roster and history was made

After the Missispppi state game the Ramblers defeated Illinois, 79-64 in the Mideast Regional, which pushed them to the Final Four in Louisville, Kentucky. In the national semifinal, Loyola beat Duke, 94-75 behind a 29-point, 18-rebound game by Les Hunter. Thus, the stage was set for one of the most thrilling championship games in NCAA history.

On Saturday, March 23, 1963, the odds were stacked against the Loyola Ramblers. Despite being the top offensive team in the nation and scoring 100 or more points 11 times during the regular season the Ramblers were labeled as underdogs as they faced the two-time NCAA champion Cincinnati Bearcats. as predicted, Cincinnati's style of play caused problems for the Ramblers from the tip-off. By the second half, with 13:56 left on the clock, Loyola was trailing by 15 points, 45-30. The Ramblers were so out of their normal rhythm that their star, Harkness, had not yet scored a single point. Against all odds, Loyola's stormed back to pull within two points. then Loyola All American Harkness gave the TV audience a treat, scoring 11 of his 14 points in the final five minutes. His 12-foot jumper with four seconds remaining in regulation tied the score at 54 and forced overtime.

As the compelling story of the strong-willed underdogs unfolded in Freedom Hall, the Ramblers were cheered on by fans from Duke and Oregon State, who had lost their Final Four games. Ireland later recalled, "We didn't have a band, but the Duke band got behind us."As the game went into overtime, a Harkness layup gave the Ramblers a quick lead, but the Bearcats answered with a basket to tie the game at 56. A 20-foot jump shot by Ron Miller gave Loyola the lead. With 1:49 remaining and the game tied at 58, Ireland called a time-out to set up a play, which was forced into a jump ball by Cincinnati's Larry Shingleton.

Loyola's shortest man, John Egan squared-off against the taller Shingleton to see who would play for the last shot in the pre-shot clock era of college basketball. To the amazement of the fans and his own teammates, Egan leapt at just the right moment to tip the ball to Miller who moved the ball upcourt for the last shot.Ireland wanted his All-American, Harkness, to take the last shot, but the Bearcats' Tom Thacker was not going to let Harkness near the basket. With time running out, Harkness fed the ball to Les Hunter at the foul line. Hunter's shot spun around the rim and bounced out, but Vic Rouse, fighting through Bearcat defenders, emerged. With one second remaining, Rouse tipped the ball through the basket as the clock struck zero.

Loyola University Chicago upset two time defending champion Cincinnati 60-58 in overtime and became the 1963 National Basketball Champions. Even today, Loyola remains the only school in Illinois to have won a Division I National Championship in basketball. The five Iron Men -- Jerry Harkness, Les Hunter, Vic Rouse, John Egan and Ron Miller -- have each had their jersey numbers retired. On Sunday, March 24, the front-page headline of the Chicago Tribune provided the perfect footnote to the magical season: "Loyola Rules U.S."

Do the Right Thing

61 years later, that NCAA tournament regional semifinal game between Mississippi State and Loyola has been all but forgotten, rendered a footnote to our racial, social and athletic history. The significance that was present in that moment has eroded over time but it shouldn’t have. Every lesson we learn as human beings shouldn’t have to include racial strife and bloodshed sometimes both sides just need to do everything in their power to simply do what’s right.